David Byrne: stay hungry

By Richard Grant, The Daily Telegraph, 16 March 2009 [Link]

Photo by Danny Clinch

There is a muffled cry from within the hotel suite and then a startled, barefoot, shirtless David Byrne opens the door with his white hair standing on end. 'Oh,' he says. 'Wow. I was at this museum and wow, um, well, maybe if you don't mind, I guess we could talk while I pack.' The suite is a jumble of big armoured suitcases, piles of dry-cleaned clothes, camera and computer equipment, stacks of CDs, hats and shoes, a folding bicycle with a travel case.

There is a muffled cry from within the hotel suite and then a startled, barefoot, shirtless David Byrne opens the door with his white hair standing on end. 'Oh,' he says. 'Wow. I was at this museum and wow, um, well, maybe if you don't mind, I guess we could talk while I pack.' The suite is a jumble of big armoured suitcases, piles of dry-cleaned clothes, camera and computer equipment, stacks of CDs, hats and shoes, a folding bicycle with a travel case.

Byrne is five months into an 11-month world tour and the bicycle is a key component of his portable lifestyle, allowing him to escape the touring musician's trap of hotel-venue-bar-hotel and explore the parks, museums, art galleries and CD shops of whatever city he happens to be in. Today, it is Seattle and he has just cycled back from an exhibition of antique court miniatures from Rajasthan. 'Very cosmic stuff,' he says, pulling on a grey collared sweater and failing to notice that it is inside-out. 'Feet with silver rivers coming out of them and wrapping around the multitudes. Very nice and very hard to know what they all mean.'

He is touring because he loves to tour and perform live, and a convenient excuse to get back on the road has presented itself. Byrne released an album last autumn called Everything That Happens Will Happen Today and it is his first collaboration with Brian Eno since 1981, when they opened up a new genre of music with My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. A sound collage of spiky funk rhythms, weird electronic noises and recorded snippets of American radio preachers, Arabic singers and chanters, an exorcist and other 'found vocals', as Byrne and Eno called them at the time, Bush of Ghosts helped usher in the era of sampling and loops.

Except for a few blurts, clicks and hisses, the new album sounds nothing like its historic predecessor. Byrne sings his own lyrics this time, in a voice that sounds surprisingly tender and heartfelt compared with the neurotic, slightly strangulated style that made him famous with Talking Heads. And Eno, who produced three albums for Talking Heads (More Songs About Buildings and Food, Fear of Music and Remain in Light), pioneered electronic ambient music and has lately been producing megahits for Coldplay, has come up with a fairly conventional set of catchy pop arrangements.

'We're calling it electronic folk gospel,' Byrne says, transferring immaculately pressed short-sleeved shirts from a broken suitcase to a new one. Underneath the shirts, he finds a pair of clear plastic sandals and holds them up. 'We were in Singapore so I've got all this hot weather stuff,' he says. 'Sandals, sun block… won't be needing these any more. Still, no sense throwing them away.' He tries to get back to the point he was making but it is not quite available to him now, so he stares out of the window, holding the sandals, waiting patiently for his thoughts to arrange themselves and the words to return, looking like a man who has gone through this process many thousands of times and grown comfortable with it.

'But yeah,' he continues. 'After I got Brian's tracks, I kept them for a long time because I was probably a little afraid of how to begin, not because I didn't like the tracks, but because I thought, Oh, there's going to be expectations. People are going to think it will be Bush of Ghosts 2 or Remain in Light 2. Or they're going to expect the same sense of surprise that those records gave them at the time, and I didn't want to compete with that.'

From the broken suitcase he pulls out a green apron with a cartoon of a fat, slavering chef on the front. 'I've got lots of souvenirs!' he exclaims. 'They were giving these aprons away free in Wellington if you spent more than $10 at this pharmacy and I thought, I need a cooking apron, and look at the label, this one is 100 per cent polyester!'

He laughs heartily, exposing perfect white teeth. 'But yeah, eventually, having listened to a few of Brian's tracks, over and over again, I said, "Brian, this is the vibe I'm getting. The chords and the chord changes you're using are giving me a kind of gospel feel." And of course at the same time it was very electronic sounding. I said I would write words to go in that direction and that's pretty much how it happened.'

There is still a peculiar, slightly absent quality about David Byrne, but he seems a lot more comfortable in his skin than he used to be in the Talking Heads days, at the height of his fame, when interviews would sometimes send him into a twitching, writhing, tongue-tied agony. He is 56 now and he has aged well. The passing years have been kind to his face and his body and given him a grace and dignity that he wears lightly and unaffectedly.

He divorced his costume designer wife Adelle Lutz in 2004 – they have a 19-year-old daughter, Malu – and his current girlfriend is the artist Cindy Sherman, who, as Byrne puts it, 'takes photos of herself that you would never recognise as her'. She has been on tour with him, with her own folding bicycle, but she flew off to Berlin yesterday to open her latest exhibition there. 'We've been together a couple years now,' he says. 'That's pretty good, knock on wood.'

He still has a tremendous, omnivorous appetite for the latest thing in music, art, books, film, culture, technology, and his own creative energy seems like a marvel from an outside perspective, although he sees it as something steady, plodding and reliable. 'I never get stuck or run out of ideas, but I don't always hit the peaks. But I also know that if I sat and waited for a great inspiration to come, I might be waiting for a long time. You have to be active, to get the ball when it comes, in the game, it's flying, it's not – somebody made a metaphor something like that.' He pauses and waits. 'So yeah, keep busy, just keep doing it and every once in a while I say, "OK, that might last. That's a keeper." '

At present, he is collaborating with young, experimental groups such as Dirty Projectors and Arcade Fire. He has kept a finger on the pulse of the dance music scene and is now working with the New York band Brazilian Girls, the superstar DJ collective NASA, and producing a 22-song disco opera about Imelda Marcos with Norman Cook. 'Oh, Imelda loved disco,' he explains. 'She spent a lot of time going to the clubs in New York and she actually converted a floor of her house into a kind of nightclub with the mirror ball and everything, so it seemed like a good way to get into her story. The songs are all written but we've got 22 different singers so it's taking a while to finish.'

Then there are his film soundtrack albums, his photography (14 books published so far), his writing, the record label he founded and a more or less constant stream of art projects. Most recently he transformed a disused building in Manhattan into a musical instrument, attaching hammers to the pipes and girders, fitting compressed-air hoses in the plumbing, and wiring it all into the keyboard of an old pump organ and inviting the public to 'play the building'; in August, to his great excitement, he will be doing the same thing to the Roundhouse in London. He has also found the time to design a series of conceptual bicycle racks for the New York City Department of Transportation, one in the shape of a dollar sign for Wall Street, another like a high-heeled shoe outside the Bergdorf Goodman department store, and so on.

Ross Godfrey of the band Morcheeba, who worked as a co-producer on one of Byrne's solo albums, describes him as 'a renaissance man living in the future who is a bloody workaholic and makes everybody else look lazy and out of touch. He is a much-needed figure in the tumultuous times we live in. He lives his art and he has been a guiding light in the music industry for many people keen to move on from the now-dead model of business.'

Byrne, whose words come out a lot more crisply on the page than in person, and is a lot more pragmatic and astute than one might expect, wrote a very influential article for Wired magazine last year about the various business strategies available to musicians in the era of free downloading. In general, he is optimistic about the future of music and musicians, although not the future of big record companies.

'People are already finding ways to make their music and play it in front of people and have a life in music, I guess, and I think that's pretty much all you can ask,' he says. 'They might never get to the point where they're a serious threat to Coldplay, let's say, but in most cases that's not their ambition anyway. The difference now, with the production and distribution costs being so minimal, is that you can survive on the small scale, whereas before you needed to get up into the big leagues to survive.'

He packs up his camera and folds his laptop shut. He puts on a pair of socks. He zips up one of his suitcases and then remembers to double-check the bathroom. He pads in there and, sure enough, finds two items in the shower. He finishes packing, checks his watch and then sits down facing me with both feet flat on the floor and his body in perfect symmetry, absolutely motionless except for the restless, evasive, lustrous brown eyes.

David Byrne's artistic sensibility – the perpetually bemused outsider, quirky and faux-naive, 'making the ordinary dramatic and the dramatic ordinary', as he once said – has obviously been influenced and reinforced by his 30 years in the art and music scene of downtown Manhattan, where he still lives, but he traces its genesis back to his childhood. He was born in Dumbarton, Scotland (a point of pride, like his British passport), and came to America with his parents at the age of two. Growing up in the Baltimore suburbs, listening to his parents pointing out the strange and different ways in which Americans did things, and often having to translate his parents' thick Scottish accents so that other people could understand them, he not only felt like an outsider but found it impossible to take seriously the concept of 'normal life'.

It comes as no surprise to learn that he grew into a loner who sought refuge in pop music and became obsessed with it. Social interaction was so difficult and frightening for him as a young man that he wonders if he had borderline Asperger's syndrome, a mild form of autism, and whether he cured it by performing music. He formed Talking Heads in 1975, having dropped out of art school in Rhode Island and reconnected with two of his art school friends in New York City.

With Tina Weymouth on bass, Chris Frantz on drums and a scrawny, geeky, bug-eyed Byrne on guitar and vocals, wearing sensible shirts and narrow ties amid all the leather and chains, the band made its name at CBGBs, a now-defunct downtown Manhattan club that also produced the Ramones and Blondie. A fourth Talking Head, Jerry Harrison, later joined from the band Modern Lovers, and the label art-rock became affixed to the group. They had more of a dance groove than their new-wave contemporaries and Byrne was writing and singing clever, ironic, angst-ridden lyrics.

'I really had a lot of trouble functioning socially at that time,' Byrne says. 'But I could blurt out my ideas and my feelings on stage, as well as just being up there saying, "Look at me, listen to me, I've got something to say. I'm somebody and I've got something and this is the only way I can talk to you. We can't really have a conversation, I'm afraid." ' He laughs at the memory and says it took many years but eventually the fear of social encounters just started to go away.

'I'd like to credit therapy or some of that sort of stuff, which I did for a little bit, but it was probably time more than anything else. And luckily for me, being a performer and a creative person whose work was kind of accepted, it meant that people would come up to me – girls and other people – because they were interested in what I was doing. It was still terrifying but that part of breaking the ice was in some cases taken care of. Phew, yeah. Although after a while you realise that you don't only want to talk to people who are fans, that it might not necessarily be a good idea.'

Talking Heads had a long, fine run, leaving behind eight studio albums, two live albums and Jonathan Demme's concert film Stop Making Sense, which immortalised Byrne as a palsied white man dancing as if trapped in a preposterously big suit. He wore it, he says, with a typically disingenuous piece of logic, because he wanted his head to look small. In 1991, at Byrne's insistence, Talking Heads split up amid bitter acrimony. Tina Weymouth in particular had some very harsh things to say about him and she said them loudly and publicly, that he was 'controlling', 'incapable of returning friendship', 'a vampire' and even 'a murderer'. He looks back at it now as a bad divorce that happened nearly 20 years ago.

He has now made eight solo albums and toured behind them all, but only recently has he become enthused about playing Talking Heads songs again. 'Enough time has passed now,' he says. 'And on this tour it's the Eno connection. I realised we weren't going to be able to just play the new stuff, so we tie in some old stuff from Bush of Ghosts and from the three Talking Heads records that Eno produced. It always puzzles me because you wouldn't go to see a playwright's work and expect to hear the best bits from all his plays. But when you go to see a pop songwriter's work, that's what you expect. But it's fine. We've really been enjoying ourselves and that's why we're making it such a long tour. We just agreed to do a date in Istanbul.'

With his suitcases packed and his sweater still inside-out, Byrne puts on a deerstalker hat, a hooded woollen coat and a pair of black-and-white golf shoes with the spikes removed. 'They're just comfortable shoes, sorta stylish I guess. If you like, you can walk over to the venue with me.'

He has sold out the 2,500-seat symphony hall and on the way there Byrne talks excitedly about Brazil, where he took his first real holiday in a very long time and stayed with his friend the singer Caetano Veloso, and bought nearly 100 new CDs. Through Luaka Bop, the record label he founded in the late 1980s but no longer runs, Byrne has done more than anyone to introduce the rest of the world to the great Brazilian auteurs such as Veloso, Tom Ze and Os Mutantes. His latest enthusiasm is Japanese folk music as reinterpreted and absorbed by its rock and pop musicians, and he went on another enormous shopping spree for CDs in Tokyo, uploading his favourites to his website, davidbyrne.com, and then packing them all in a crate and shipping them home.

Jim White, an alt-country singer on Luaka Bop who has toured extensively with Byrne, says, 'I've never met anyone who loves music as much as him. Every town we'd come to he'd get on his bike and ride to the record store, ask what was interesting that he couldn't hear anywhere else, buy dozens of obscure CDs, and listen to every one of them on the tour bus.'

When we get to the Symphony Hall, a security guard directs us down through various stairways, lifts and corridors to the dressing-rooms, where many pairs of white shoes are lined up neatly; in Byrne's room there is a piano, three lemons and the biggest root of ginger I have ever seen. Colds and flu are a constant menace to touring musicians and Byrne swears by his homemade ginger and lemon tea as a preventative.

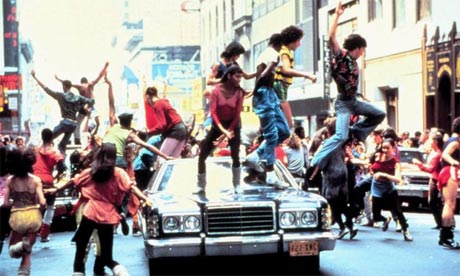

The last time he toured he had a six-piece string section. This time he has three dancers, three backing singers, a drummer, keyboardist, a percussion prodigy and a wickedly funky bass player who used to play with Chaka Khan and Nile Rodgers. There is no support act and when they take the stage, all dressed in white, with Byrne front and centre at the microphone, the audience sets up an ecstatic roar of applause that goes on for a full five minutes.

'Wow,' Byrne says as it finally starts to subside. 'I'm going home now. I got what I came for.' Then, and it is noticeable how much more fluent, confident and chatty he is in front of 2,500 strangers, he lays out what he calls 'the menu' for the evening's entertainment – a sampling of all the work that he and Brian Eno have done over the years. He counts off the introduction and the band kicks in to Strange Overtones, a self-deprecating pop-funk song about writing a song. 'This groove is out of fashion,' he sings. 'These beats are 20 years old.'

Two hours later, after a joyful, radiant, applause-drenched performance, and a fourth and final encore for which Byrne and all the dancers and musicians wore frilly white tutus, the drinks are flowing backstage and everyone looks flushed and giddy. Byrne, with people all around him, camera flashes going off and a hand-rolled cigarette tucked behind his ear to smoke later, is laughing and grinning like a man on top of the world.

He sits down with a fresh beer, and a radio DJ is asking him about the psychedelic African music he has collected and released on Luaka Bop, and someone else is asking about the documentary he made about the chicken-sacrificing Candomblé religion in Brazil, and then I ask him about a little thing I noticed in the sleevenotes to the new album, a reference to a book called What Is the What?, the fictionalised biography of a former child refugee from Sudan by Byrne's friend Dave Eggers.

'Oh, I was thinking about that book all the time while I was making this record,' Byrne says. 'Valentino, the Sudanese guy, goes through all kinds of unrelenting horrors, but he's eternally hopeful and even cheerful, in a way that defies all logic, and I wanted to get some of that spirit of resilience in the music. In the end that's what humans – and animals too, I guess – are all about. They go on, despite everything.'

Later, most of the dancers and musicians reconvene at a place with no name, no windows and a pink door. Behind the door is a man with a walkie-talkie and some stairs and a corridor and another door that opens into a nightclub set up to look like an old speakeasy. On stage are three men dressed in 1930s suits, singing 1930s songs in close harmony and accompanying themselves with ukulele, stand-up bass and drums. Byrne, back in his deerstalker and golf shoes, is standing at the bar with a pint of ale and a big smile on his face, moving his head and shoulders to the clickety-clack rhythm and singing along with the words. People are trying to get a word with him about this and that, and I try, too, but he just laughs and grins and says, 'These guys are great!' and then goes back inside the music.

There is a muffled cry from within the hotel suite and then a startled, barefoot, shirtless David Byrne opens the door with his white hair standing on end. 'Oh,' he says. 'Wow. I was at this museum and wow, um, well, maybe if you don't mind, I guess we could talk while I pack.' The suite is a jumble of big armoured suitcases, piles of dry-cleaned clothes, camera and computer equipment, stacks of CDs, hats and shoes, a folding bicycle with a travel case.

There is a muffled cry from within the hotel suite and then a startled, barefoot, shirtless David Byrne opens the door with his white hair standing on end. 'Oh,' he says. 'Wow. I was at this museum and wow, um, well, maybe if you don't mind, I guess we could talk while I pack.' The suite is a jumble of big armoured suitcases, piles of dry-cleaned clothes, camera and computer equipment, stacks of CDs, hats and shoes, a folding bicycle with a travel case.